Cold-Sensitive Bedding Plants

For the last several years, one of the floriculture research thrusts at Michigan State University has been to better understand how temperature controls growth and flowering of bedding plants. Former graduate students Matthew Blanchard, Lee Ann Moccaldi and Tasneem Vaid generated a substantial amount of research-based information that quantifies how plants flower at a range of greenhouse temperatures. This information can be used in several ways, especially to improve scheduling accuracy and, with Virtual Grower, greenhouse energy efficiency.

Fortunately, the price of natural gas has decreased in the last several years, resulting in lower heating bills. However, a substantial amount of energy is still consumed to heat greenhouses, which notoriously have poor insulation. One way to reduce energy consumption for heating — on a per crop basis — is to grow plants with similar temperature responses together, and grow crops with a different temperature response at another temperature. Of course, this requires separate greenhouse sections that can be controlled individually.

We have been categorizing bedding plants based on their base temperature, which is estimated using flowering time data. The base temperature is the cool temperature at which plants stop developing. Plants that have a relatively high base temperature (46¡ F or higher) are labeled as “cold sensitive” and those with a low base temperature (39¡ F or less) are “cold tolerant”. Those that are in between this range can be called “cold intermediate”. This means that at low temperatures, cold-sensitive plants develop very slowly.

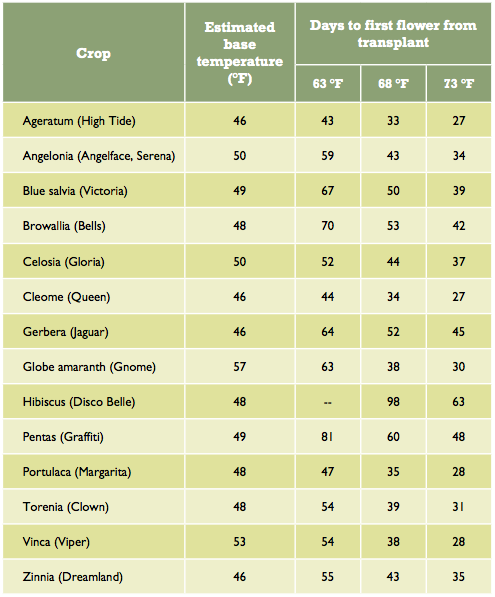

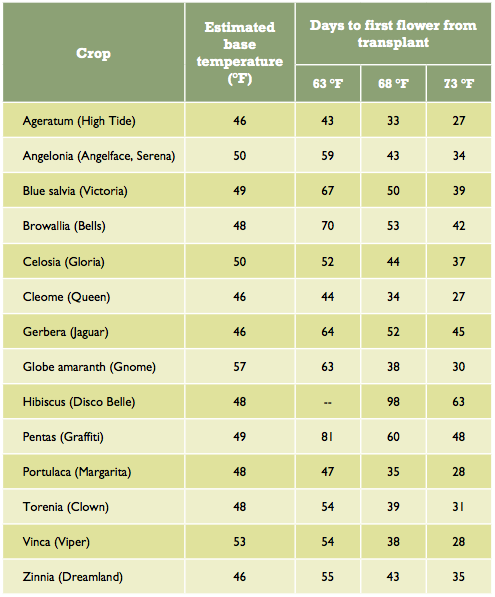

Table 1 (below)shows a list of bedding plant crops that are considered cold sensitive based on their estimated base temperatures. For most of the cold-sensitive crops, flowering takes 50 to 70 percent longer when grown at 63¡ F than at 73¡ F. More information can be found in the FlowersOnTime spreadsheet, which can be downloaded under the “Grower Resources” tab of the Floriculture Research Alliance website: www.floriculturealliance.org. This spreadsheet can be used to predict the consequence of increasing or decreasing production temperature based on your typical crop time and temperature setpoint, helping you decide at which temperature to grow crops.

Therefore, cold-sensitive plants should generally be grown warm (70 to 75¡ F) to reduce crop production time and, in many situations, reduce the amount of energy consumed for heating on a per-crop basis. (For more information on this concept, visit www.flor.hrt.msu.edu/temperature). An additional benefit of growing cold-sensitive crops warm is a higher temperature promotes active growth, which can reduce plant susceptibility to pathogens. In addition, some cold-sensitive crops, including celosia and hibiscus, become chlorotic when grown at low temperatures (less than 60¡ F).

Table 1. Cold-sensitive crops (with series tested in parentheses), their estimated base temperatures, and times from transplant to first flowering at three average daily temperatures with a long-day photoperiod. These crops grow slowly at low temperatures and so in many situations, should be grown at a warm average daily temperature (above 70 ¡F).

Video Library

Video Library