Scientists Tackle Rose Rosette Disease

Halfway through a five-year, $4.6 million grant to combat rose rosette disease in the U.S., a national research team studying it is encouraged by the amount of information learned but admits having a way to go before finding how to overcome the deadly problem.

Rose rosette was observed on wild roses as early as the 1940s, but it was not until 2011 that scientists definitively identified the cause as being from a new virus in the novel genus Emaravirus transmitted by the microscopic eriophyid mite, according to David Byrne. Now the virus is killing commercial rose varieties.

Symptoms, which can show up as early as 17 days from exposure to infected mites or as many as 279 days after, include “witches’ brooms, excessive thorniness, enlarged canes, malformed leaves and flowers.” Ultimately, the rose plant dies.

The team is pursuing three issues: the virus, the mite and rose plant resistance to the disease, according to Byrne, professor of Rosa and Prunus Breeding and Genetics for Texas A&M AgriLife Research, College Station, and Rose Rosette Disease Project director. And now they are soliciting help from people who like to grow roses as well.

“We’re still learning about the mite and the virus,” Byrne said. “And now we are seeing rose rosette not only on multiflora (wild) roses, which are considered invasive, but also on commercially cultivated roses.”

Because of that, researchers now consider all roses susceptible to the disease until proven otherwise. That calls for a massive monitoring effort, he said.

He said as the national research project begins its fourth year, the field trials planted the first year are just now providing data that could lead to developing resistant varieties.

“We’re up to about 500 different roses planted for evaluation, and I also have collected data on probably close to 700 already. The vast majority are susceptible,” Byrne said. “We’re in the verification mode now, because some varieties that had been thought to be resistant are turning out to be susceptible.”

The researchers are turning to molecular techniques to develop markers to use in the analysis for marker-assisted selection for breeding, which theoretically can decrease the breeding cycle by half, he said.

“What’s more important is we can decrease by 80 percent the number of plants we have to put out in the field,” he said. “That is a huge saving and potentially will allow us to look at more seedlings, which will accelerate the breeding process as well.”

The team also is trying to develop better tools to detect the virus and presence of the mite.

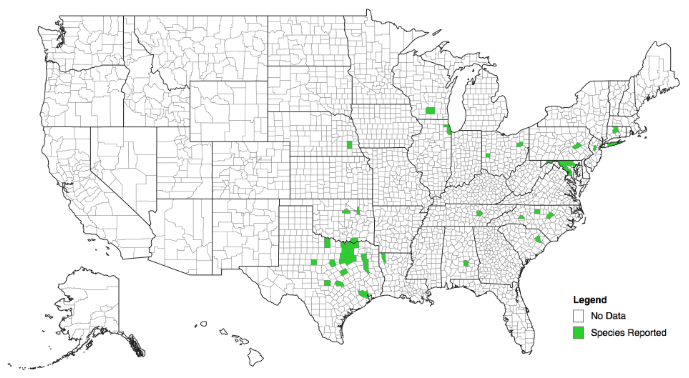

To track the mite, all the reports of rose rosette have been put on a map to get a sense of the mite’s distribution and movement, Byrne said. Researchers know that the microscopic mite travels in the wind and has been known to move 300 feet a year. There appears to be a northern and a southern range, which in Texas is roughly at Interstate 20, below which cases of rose rosette are rare.

“In the last two or three years, we have confirmed it in some Texas counties south of I-20, but it might’ve just been brought in from somewhere,” Ong said.

“It’s been exciting to see this national effort come together,” Byrne said. “We are trying to understand the epidemiology and environmental factors of the disease development and spread. Hopefully, we will have even more information by the end of this year.”

Video Library

Video Library